The Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna is one of the nicest museums I have visited. We had been there before but this time the explicit reason was to study the paintings of Archangel Michael by Gerard David, Luca Giordano and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo. I didn’t find the latter but the museum offered plenty compensation. The Kunsthistorisches Museum has a wonderful collection, splendid curation, a great building and cosy couches in ideal positions.

The museum allows one to get very close to the paintings. The alarms don’t go off as quickly as in some other places and many works are not covered by glass. This is enormously risky in terms of potential vandalism or accidents but it’s wonderful for students like me.

The two Michaels

Gerard David: Altar of Saint Michael

When I entered Room 20 I had to steady myself. The small room is filled with Flemish Primitives, many of which I’m familiar with from reproduction. I knew I was going to spend some time here. I don’t even need to look at the works. Merely being in their presence feels like arriving in a spiritual home.

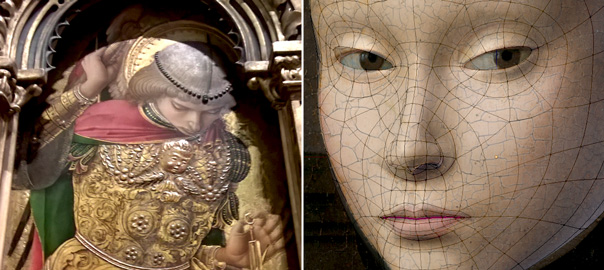

One of the paintings that I wanted to study is in this room too: Gerard David’s Altarpiece of Saint Michael, painted around 1510. The triptych consists of a squarish center panel depicting the archangel defeating demons, flanked by two tall panels each depicting a saint holding a book. On the left, judging by the lion at his feet, is Saint Jerome (amusing combination for me since my brother’s name is Jerome). On the right a man dressed as a monk holding an open book upon which a little naked person is kneeling in prayer. I imagine that little guy to be the Virtual Reality user experiencing the diorama.

Of course the middle panel absorbed my attention. What a glorious composition! The depiction of the archangel controls the picture aesthetically. His figure holds everything in place and he seems completely at ease, leaning on a solid golden section. His spread wings remind of a crucifix. In fact, each of the main figures in the three panels is holding a long staff with a crucifix at the top, together referring to the crucifixion scene on mount Golgotha.

Michael’s face is deeply serene. Its angelic androgyny contributes to that serenity. This is especially striking because of the contrast with the vulgar and grotesque demons beneath him. As is common in the Middle Ages, the devils are portrayed as monsters. There’s seven of them, which might remind of the cardinal sins, according to the museum’s description.

The most remarkable aspect of the action is that Michael doesn’t even harm the demons. He just covers them with his enormous velvety cape: a heavy blanket under which he seems to put the monsters to rest. Almost like putting children to bed, reminding somewhat of virgin and child scenes or even an allegory of charity. He has no weapon. Just a shield and a staff.

The figure of the archangel in this work inspires admiration. He’s not depicted in the usual more symbolic, removed way. Here he feels more like a saint: you want to be like him. Just like Michael, I feel I must confidently and precisely suppress evil. Without emotion. Just do it because it’s right. Like brushing your teeth before bed. Only infinitely harder. Hence the admiration: I wish I could be like him. I know I should try to be more like him. But I also know that I can never achieve this ideal. He remains a inspiring saintly example.

In the background we see three angels seemingly sweeping up hords of demons. Almost like a mundane housekeeping task. Just doing the work.

Of note is that the demons are not cast into some vulcanic pit of hell. But apparently down to earth. Is earth hell?

More thoughts in Room 20

I found another depiction of the Archangel Michael in the same room in the tiny Maria with child by Van der Weyden’s studio: a decorative architectural ornament depicting Michael with raised sword chasing Adam out of Paradise.

On the other side of the room, two larger panels by Hans Memling depicting Adam and Eve. I was especially struck by their faces. They look so fresh. Surprised. Filled with wonder. Have they just been crying? Have they just been born? Innocent beauty (right before biting in the apple they are holding). Very naked.

And there’s much more in the small room! A triptych by Memling of the Madonna flanked by the two Johns, an intense crucifixion by Van der Weyden featuring Magdalena and Veronica, remarkable dark blue angels and a fantastically imaginary Jerusalem in the background, a small diptych by Hugo Van der Goes with a fall of man and a deposition, some wonderful portraits by Juan de Flandes, and several more small pictures.

Suffice it to say that I didn’t make it. I didn’t succeed in observing every painting in Room 20. It’s all so intense. Luckily Room 13 next door has comfy couches and walls plastered with Rubens. The irony of such spectacular work having a relaxing effect!

Luca Giordano: Saint Michael vanquishing the devils

Of an entirely different order is Luca Giordano‘s gigantic painting of Saint Michael vanquishing the devils, hung impressively central in a huge room. Painted around 1666 in Italy this is a highly baroque picture with diagonals and spirals swirling over an otherwise fairly static symmetrical composition. Typically for the more modern approach to painting, the work is very narrative, with realistic depictions of humans representing allegorical themes. And it’s intentionally spectacular.

The painting is so large that standing close to it means that I join the devils at the bottom with Michael towering over me as well as them. This painting represents an entirely different approach to religion. For David, the archangel is an inspiring caretaker, for Giordano he is a powerful warlord.

Even more than Raphael’s Michael that I explored in the Louvre last month, Giordano’s seems to dance on top of the demons. Despite of the raised sword, he doesn’t appear emotionally involved in a battle. He’s doing a dance. Going through the motions. Certain he will win. That is the will of God, after all. He is just performing the eternal ritual. The effortlessness of tiptoed balancing on the devil seems to mock all illusions that evil ever had any chance of winning.

It’s not an intimate scene. The light triumphs over the darkness. Simple, clear. Cherubs in the sky. Devils on the ground. The red glow below seems to suggest an underworld, not the surface of earth. Behind the angel the clouds break open to let the divine light stream in. Everything is yellow, brown and red. Michael stands out with blue and green garments inspired by Roman armor.

Typically for the modern era, the devils are depicted as almost humans. Only their little horns, small bat wings, pointy ears and long nails signify them as evil. Giordano also has Satan mimic Michael’s pose with raised arms and spread legs and wings, reinforcing the notion that the two are brothers. Typically Lucifer is naked and Michael dressed.

Unsurprisingly with sensual work like this it’s easy to read a erotic undertone in the scene. Michael is offering Lucifer a look under his skirt but Lucifer turns his head away. This causes Michael to blush. Michael is wielding a red hot sword (a flaming phallus). He’s also very feminine: skirt, cape draped like a shawl, long curly hair, graceful pose, feather on his hat.

Curiously Lucifer seems to have been sitting on a chair -a throne?- when Michael attacked him. Maybe the other devils were carrying it.

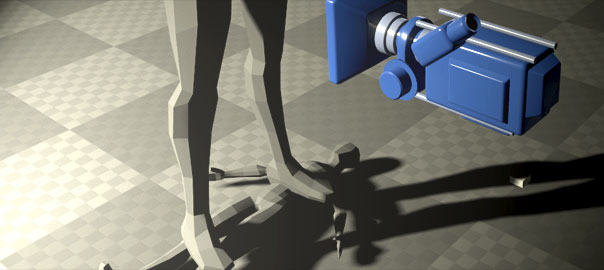

The work struck me as a depiction of a three dimensional scene that the artist imagined. Even if that scene is hard to read here and there, it is the unseen three dimensional reality that matters. Very much like realtime 3D.

More museum musing

Perugino and Raphael

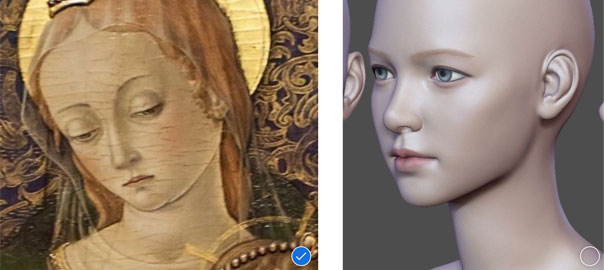

Seeing the multiple Perugino paintings in the museum’s collection I suddenly understood the desire for pre-raphaelism. Raphael’s work is undeniably beautiful, clever and sensitive. But his teacher’s work still holds the mystery of the primitives. There is magic in Perugino’s worlds. Mystery. Awe.

That makes them harder to appreciate. Raphael is easier on the eyes and mind. But Perugino shows us the true holy essence of existence. And sometimes we just don’t want to know how devastatingly dazzling our existence is. Raphael distracts us from being too acutely aware of this. He consoles with the charm of mundane prettiness.

Perugino is stubborn. He’s not fishing for compliments. Not trying to make your life easier. He’s a hardcore painter of an irrefutable truth that is agonizingly mysterious.

If you mock a Perugino or have fun in its vicinity you will most certainly be struck by lightning. That’s what the eyes of his figures seem to say. They force you into sincerity. And it’s a pleasant sensation. To be allowed to be sincere.

If the Raphael is the exquisitely well made entertaining blockbuster then the Perugino is the annoyingly obscure clumsily shot art house film. Ridley Scott versus Chantal Akerman. Guillermo del Toro versus Andrei Tarkovsky.

Rewarding attention

One of the things that I admire in the Flemish Primitives is their devotion to detail. Unlike later painters, they eschew suggestion. Everything in their paintings is actually there. When you observe closer, you see better. As opposed to baroque painting for instance where zooming in only reveals a paint stroke (admirable effect in and of itself, of course).

This necessity for things to actually exist feels similar to the requirements of computer-based realtime 3D. I have long been annoyed by the difficulty of simply suggesting shapes in my medium. But the Old Masters are helping me to embrace this aspect and teach me how to use it.

Extreme detail in art gives a feeling of preciousness. It demands reverence, respect. And, importantly, it rewards the viewer for paying attention! The more you look, the more you see. The closer you look, the better you see.

This is not exclusive to the Northern Renaissance. The Italian mannerist Bronzino also rewards attention. Getting closer does not disappoint. Like in the work of the Flemish Primitives, the closer you look the more you see. It’s always sharp. The picture never dissolves into brush strokes. At least to the naked eye! Of course brush strokes are revealed when we blow up technical reproductions. Demonstrating how the art is made to the scale of the human body. Just like Virtual Reality.

You must paint individual hairs!

More Michaels

That evening we attended a violin quartet performance in the baroque Saint Anna church. They played an early piece by Vienna’s superstar Mozart and a wonderful rendition of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden.

Right above our heads, like a sign from heaven, a glorious Archangel Michael chases a bunch of devils out of heaven with firy lightning bolts in each hand. Again dancing on tiptoe.

The next day we went back to the museum. I still felt somewhat drained from the intense experiences in Room 20. So I strolled around the museum more leisurely, and visited the musical instrument collection, the Greek and Roman collection and the decorative arts section, before diving into the picture gallery.

There’s a room filled with paintings by Bartholomeus Spranger, a unique Flemish mannerist painter. His work is extremely erotic. It is simply custom in his world for women to bare their breasts. Even when they are otherwise fully dressed. So too his Minerva victorious over Ignorance which feels a bit like a Michael vanquishing Satan. Except, of course, typically for the time, it is wisdom that triumphs, not faith.

I found another Michaelesque scene in Zucchi’s Immaculata. In it the virgin moon goddess stands on the head of a devil.

There’s a wonderfully refined sculpture by Johann Schnegg in the Kunstkammer. The figure of Michael is carved in ivory while Satan is made from ebony. Satan gets to have feathered wings rather than the usual bat wings. As opposed to their static appearance in many depictions, here Michael’s wings seem very much a part of his body as he raises one together with his right arm. And even in these delicate materials, Michael balances on one foot on a devil lying on a cloud covered globe.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save