When I started considering VR for new creations at Tale of Tales, I didn’t imagine a very big distinction between our previous work in realtime 3D (artistic videogames) and what we would do in VR. After all, I never thought of our work as screen-based exactly. For me what mattered was the creation of a living world on the processors and in the memory of a computer. The screen was just a way to show this world to a human.

So initially I thought of VR as just another screen, another way to see the worlds we create, not essentially different. But I was wrong. Even after only a brief period of investigation and prototyping it has become clear that the VR headset turns the computer into an entirely different medium! Everything is different in VR, few of the old conventions or habits are useful, nobody really knows how to use VR well yet. It’s as exciting as it is annoying.

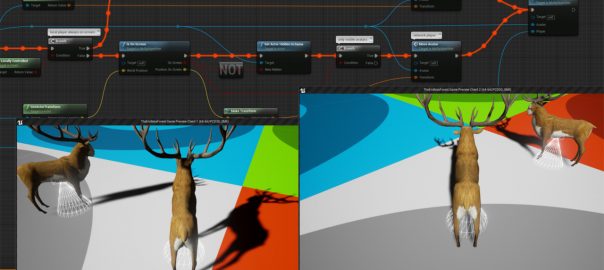

What follows is a list of observations made in the last six months working on our project Cathedral-in-the-Clouds, an attempt to fuse the sacred and cyberspace in a contemplative experience. The text ends with an argument about the importance of imagination for art vis-à-vis its apparent absence in VR.

Time limits

Because wearing a head-mounted display is uncomfortable, my intuitive inclination in real time 3D to focus on the creation of open worlds must be tempered. Discomfort causes most VR experiences to be brief, and thus a certain linear design is preferable. Furthermore there is a radical rupture between being in the 3D world (while wearing the headset) and being outside of it (not wearing the headset). One cannot casually experience a VR piece. Which makes it challenging to create “art that becomes part of people’s lives”. I don’t want people to escape into our art, preferring to make a connection between the art and their bodies, their environments, their memories, their personalities.

Body size awareness

One of the things I like about VR is that it gives the user a certain awareness of their body by implying it in the 3D scene. Little of the trickery with scaling and framing that is common in videogames works in VR. Your body quite literally becomes the measure of all things. This makes working with scale very interesting: since we are all acutely aware of the size our bodies, it’s much easier to make big things look impressive, for instance.

Realism

Related to the awareness of the body’s size is the requirement of a certain level of visual realism in VR. The way we used to fake volumes and details with textures doesn’t work very well. But stylized shapes and toylike objects do. When they are realistically shaded, in fact they appear more wondrous than photographically realistic objects. The mind quickly adjusts and accepts a photographically realistic scene. But believing in the reality of something that we know cannot exist in the real world is a much more magical feeling.

Visual primacy

I don’t really feel immersed in a VR scene. Because VR is such a visual medium. The whole experience centers around what we see.

But it doesn’t offer the visual range that we are used to. A certain distance is required to see things, for instance. Things that get too close or very far become hard to see ( the documentation of the Unreal engine recommends putting VR objects in a range of 0.75 to 3.5 meters away from the virtual camera).

Another aspect of the visual nature of VR is that the only thing that matters is what happens in front of you, since humans simply don’t have eyes in the back of their heads. So despite the 360 degrees of potential, you only actually see what’s before your eyes.

Problematic sensuality

Contrary to the awareness of scale, the visual primacy in VR more or less reduces your body to a set of eyes. You become body-less, a (human-sized) ghost, a spirit. You can’t distinguish things that happen very near to you. As opposed to a third person avatar on a regular screen who is clearly immersed in the fictional scene and whom you can easily empathize with. VR feels more detached. It’s purely visual and it feels a lot less sensual.

The sensations in VR are triggered by the proximity to objects and characters. It feels very voyeuristic but you never feel embarrassed. In part, I think, because VR is so extremely private.

Uncanny safety

One interesting sensation in VR is vertigo. It feels very nice to stand on the edge of an abyss because in VR you always feel perfectly safe. Nothing bad can happen to you while you are wearing the headset. The world looks real but it cannot harm you. Paradoxically VR allows us to escape into reality. The sensations feel physically real, but you know you are always perfectly safe.

The nausea that VR can cause in a user, more or less obliges designers to be exceptionally cautious. You can’t mess with people in VR because it’s so easy to make them physically ill. This certainly reduces the palette available for artistic effects.

VR feels so real to our bodies that VR experiences need to be a lot safer than actual reality. Our mind then quickly gets accustomed to this unrealistic level of safety and basically becomes untouchable, unmovable, an impregnable fortress.

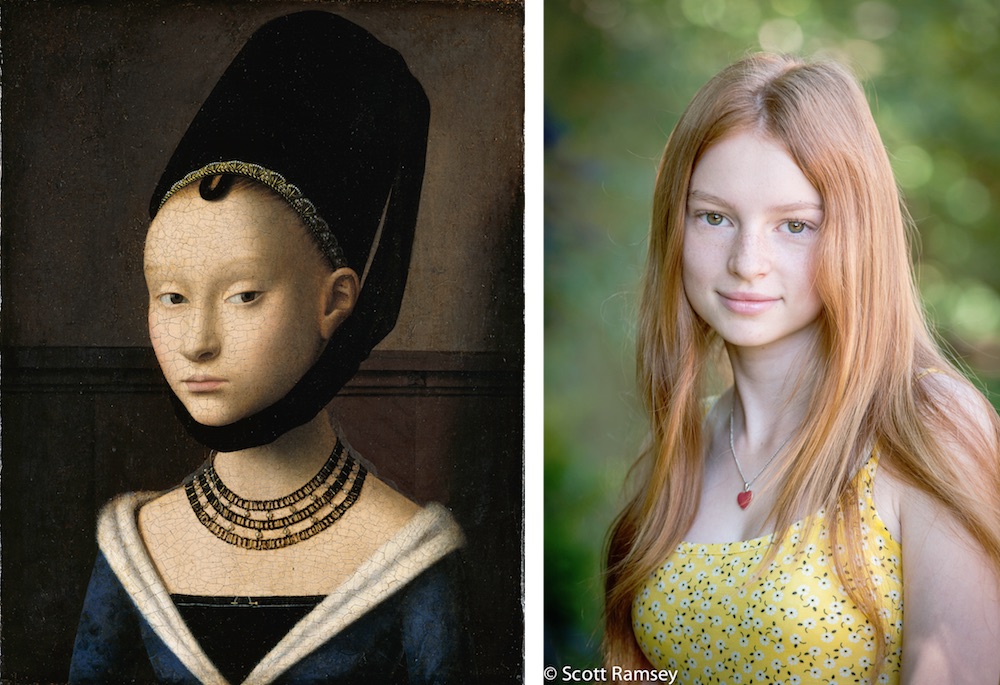

Immersion without imagination

VR is touted as the ultimate answer to our desire to be immersed in a simulation. But because VR so directly puts us in a physical environment, it bypasses the imagination that is necessary to deeply engage. It’s purely visual, purely physical. It triggers physical reactions but does not stimulate thinking or feeling. Further hampered by the awkwardness of the headset that you can never forget about.

VR, counter-intuitively, creates a distance between the scene and the spectator. You are always outside, not involved, a fly on the wall. You have no presence in the virtual world. The virtual world does not believe you exist. At least not as a person. Maybe they recognize you as a camera, an observer, someone they have no emotions or thoughts about, someone they merely tolerate (causing one to wonder about the reasons why). You’re in the middle of the action but you cannot be harmed. You are perfectly safe emotionally. If only because you need to constantly monitor how you are doing physically (am I not bumping into things in the actual space where my body is? Am I getting nauseous? Do I look weird wearing this thing? -Is someone watching me?- Mustn’t forget to fix my hair when I take it off).

The experiential realism of VR is exactly its weak point. Because art tends to affect me most where it deviates from the familiar. And art is where I find the deep emotions and thoughts. Realism creates distance. And it distracts, rather than immerses, if only because it forces our brain to be continuously amazed by the simulation, drowning all other reactions we might have.

We don’t need imagination to believe in a VR scene. But without imagination, it is much harder, if not impossible, to access the areas in our being that bring great joy and deep insight. Imagination creates an emotional bridge to the object we are observing. Without imagination, we remain distant and separate.

Artistic problems

Despite my objections, I believe wonderful things can be created in VR. Providing its artistic problems are solved. And I worry a bit about that. I have seen this before. Videogames also have an enormous amount of artistic problems and they never got solved. Artists rarely lead videogame creations. The tools are unsuitable and the corporate structures don’t allow it. And much like VR, videogames are dominated by technology. So engineer after engineer tries to solve the artistic problems. While the artists are all but chased away from the medium by press, corporations and the public alike.

So here’s to hoping that artists will be encouraged to solve the medium’s artistic problems. Otherwise, just like videogames, VR will remain unfulfilled potential driven by desire never satisfied.

—Michaël Samyn.