A rude awakening

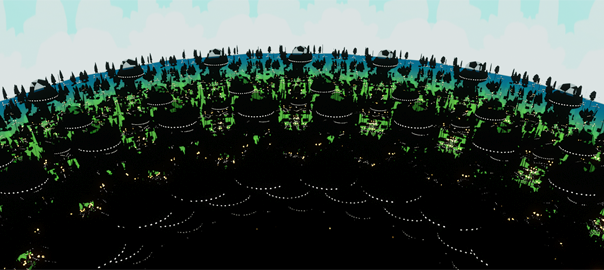

Returning to the Virtual Reality Pietà after four months, while a bit daunted by the amount of production work remaining to be done, I took courage from the idea that the design of the piece was finished. All I needed to do now was to make an epic landscape that transitions over twelve thousand years. Daunting in terms of work, but simple in terms of concept.

But then I tried the prototype.

While aesthetically appealing, I didn’t understand why this scene of a mother holding her dead son required such a spectacular context. A simple transition from day to night in a mundane scene would suffice. I also felt weary about the lesson the piece seemed to be preaching with its manipulative albeit minimal interactivity: lift the dead body in a gently embrace to make the light shine. I felt that the “now is bad, then was good” mantra, or the “we ruined the Garden of Eden” rhetoric was a bit pedantic. And all those cheap glowy lights at night looked too much like cheesy science fiction. Maybe this “edgy contrast” between a traditional religious scene and high tech graphics would increase the appeal of the piece. But how would that interest me?

Two characters in a small garden area would be sufficiently poetic and dramatic. This is how the pietà scene was always depicted in the renaissance and baroque art that I admire. That is how it is done. The strength of a pietà is its simple familiarity. It’s a modest tragic scene. The dramatic consequences should happen in the mind of the viewer, not be expressed by the art.

This is not a deposition

I had always considered this piece to include aspects of both the traditional Deposition scene (taking the dead body down from the cross, a scene that often involves many characters) and the Pietà proper (just a mother and her dead son). In the months away from the project I had developed an idea for a Deposition piece. And so i decided to separate the two. This one needs to focus on the Pietà itself.

It’s all about her sadness, it’s all about her tears. She’s cradling her dead son like a baby.

Any modern invention I might add to the pietà (and it’s easy, and seductive, to come up with ideas) does not improve the scene. We think we’re being clever as contemporary artists, but anything we would add would only reduce the impact of the work. Of course, before modernity, many artists have added new elements to the pietà scene. But, as far as I can tell, this was always done with a sincerity that contemporary artists, including myself, seem virtually incapable of. The old masters always created in service of the scene, of the meaning of the scene, even when they were showing off their skills. As opposed to today’s desire for personal original ideas that “criticize” or “subvert” or in whatever manner add something to the scene that doesn’t belong to it. Or is it just that this is the easy thing to do? The safe thing to do? To make a crude joke about a mother crying over her murdered son is safer now than expressing compassion and grief and allowing that pain to silently exist and grow in meaning.

To maximize the impact of the work, I need to not only trust my own sincerity, but also rely on the tradition of depicting this scene. My own judgement does not suffice. When I imitate, I speak with the voice of thousands. This work requires modesty and respect.

The eye does not see itself

I was also again troubled by the viewpoint in Virtual Reality. Since you do not see yourself, the environment becomes what you look at, when you are cast as the protagonist in the scene. Hence my attention to the landscape that surrounds the scene. But the fact that you don’t see yourself doesn’t mean that you don’t know which role you play! It’s not only about the environment, it’s also about who you are and who you are with.

A VR experience is profoundly awkward compared to other visual arts as it puts us in the center of the scene. It puts us in the place that we usually look at. But now this become the place that we look from. We become the subject of the artwork. And we look at ourselves.

Once you realize that the viewpoint is reversed in VR other art becomes a lot less useful as inspiration. What does a scene look like from the viewpoint of its subject? Despite of the sculptural nature of realtime 3D I’m more inspired by paintings than by statues. Because they represent worlds. But when I browse through pictures of the pietàs that have been made over the centuries I’m confused about what I am supposed to think about what I am making. I’m not making a painting, I’m making the scene that is represented in the painting. But I’m obviously not creating reality. I could consider this scene a sculpture if the spectator would be positioned outside of it. A virtual sculpture. Okay. But in this case, the spectator is the subject of the sculpture, or they are positioned in the exact place of the subject, playing its role. So is this a form of theater? Only if the actor is their own audience. And while the scene is fictional, the spectator is not. Maybe it’s like a novel written in the first person? Virtual Reality may be too real, insufficiently artificial for me to think of it in artistic terms. And yet the experience, the emotional effect, is very similar to the experience of art.

What changes when a Pietà is no longer a display to be witnessed but a scene to be experienced? There’s no need for Mary to express her grief visibly anymore. You are Mary. Your grief is that of the mother, not for the mother. You compassion is for the son, not the mother. And you think of the son as your own son, but also as the son of God, and how his death, his sacrifice means the salvation of mankind. His death is the foundation of Christianity, the philosophy that would impact Western culture more than anything. Your grief is minor in this context, and it adds an eighth sword of pain that pierces your heart.

There’s an additional dimension to a contemporary image of the Pietà. Because God, famously, has been declared dead in our era. Not just the Son, but also the Father and the Holy Ghost. And according to some, they died for the same reason: as a sacrifice for the salvation of humanity. We have sacrificed God again, this time in order to be saved by science and technology, by what we now consider truth.

The best answer is often nothing

When instead of looking at the virgin, we inhabit her body and look through her eyes, what do we see? Fortunately this is not just an aesthetic or logistical problem. What does a person holding a dead child look at? Nothing much, I presume, it’s not important, the world out there does not matter in this moment.

The way in which Caravaggio submerges his scenes in darkness came to mind.

So there would be nothing to see but the corpse in your arms? The infinite void of an empty scene in VR is impressive. There is nothing there, as far as the eye can see. I was drawn to the radical character of this idea. Although I do love being immersed in an elaborate 3D world. There could be visible objects in the immediate vicinity of the scene: the throne, the floor, plants, some objects. This would satisfy my desire to see real things in VR.

Our other VR piece Cricoterie also has a caravaggesque feeling with its black background. And in the Cathedral-in-the-Clouds prototype everything is born from emptiness. I guess I’m drawn to this aesthetic in VR. And it makes sense.

I briefly considered filling the black void with abstract decorations, perhaps expressing, supporting the feelings. But can any decoration express these better than darkness? I tried adding contemporary visuals, to express the mood, to demonstrate the vastness of the endless emptiness in which the mourning mother finds herself. But it all feels corny and out of place. I thought the contrast would be interesting but it just reduces the gravity of the piece.

I was still thinking about the simple garden scene. But after some experimentation I realized that anything out there would capture the gaze of the user. They will look at it and that will become the work of art. So I need to avoid that. Because I don’t want to “express” the emotions in the scene. Art should offer context and stimulus for the spectator’s own emotions and is not an opportunity for the artist to manipulate or impose.

What they see out there should guide them inwards. Not just towards looking down at Jesus on their lap. But towards introspection, towards being not seeing. Perhaps my goal/hope should be for the user to close their eyes. After all, a VR headset feels a bit like a blindfold. Instead of entering another world, the VR headset could enable you to enter yourself.

What would a baroque artist do with VR?

Maybe I have been seduced by power of the Northern Renaissance again, into a problem that cannot be solved in the current age. On the one hand because I obviously lack the artistic skill and on the other because we live in a time in which religious faith is not only sparse but also heavily criticized, and by no means supported universally by society. This reminds more of the Baroque times of Counter-Reformation than of the pious context in which the Flemish Primitives were active.

Maybe I should try to imagine what a baroque artist would do with this technology. How would they deal with the endlessness of simulated space? I’m attracted to baroque art because it contains a certain playfulness and spectacle that seems to fit the digital realm with its abundance, ambiguity and focus on the spectator’s experience. As opposed to the grave and solemn nature of the Northern Renaissance that was the starting point of Cathedral-in-the-Clouds and remains an important reference for the Pietà as well. How would a Baroque artist present a 15th century Pietà in 21st century VR?

To do or not to do

I still had the interaction to consider. In the previous design lifting up the body would transition the world from dark present day to bright paradise. Now I was thinking of a simple transition between day and night. Or a sort of focus: when you lift up the body, only its immediate surroundings would be lit. But the dynamics of cause and effect trouble me. I want to create endless environments, not linear stories. I want to create a context in which the spectator can explore their own thoughts and sentiments. I do not want to guide this process towards what I think is interesting. That would be a waste of opportunity and an unnecessary limitation. But I worry that if there is very little to do that causes a change the experience will feel shallow and short. If, on the other hand, there’s is nothing to do that causes any changes, it can feel endless.

I don’t remember exactly when it happened. I was prototyping all sorts of ideas and at some point I ended up in a scene completely empty and dark in front of me but with a bright landscape behind me. I had recreated the situation of the paintings: the mother with her son on her lap sitting in front of a landscape. We do not know what is in front of the protagonists. It is not depicted. But in the physical context of the museum or a church we are it, the spectators. It feels a bit like being on a theater stage with the actor peering into the darkness where the audience is. You can still lift up the body but nothing happens in the scene when you do. It should happen inside of you. You can look behind you, at the landscape, but it’s very uncomfortable, when sitting down. But it feels good to know that there is a whole world behind you while you are staring into the void of your sorrow.

—Michael Samyn.