Most of the past month was spent in Coronavirus quarantaine. The eternal city was silent as its citizens were forbidden to leave their neighborhoods. Not being able to visit churches and museums as I’m used to was tough at times. But I did not let this stop me from beginning the work on our new VR project. After all, isn’t this what we do: create virtual projects from the comfort of our homes?

Compassie is the working title for a new Virtual Reality diorama in the context of Cathedral-in-the-Clouds. The theme of the diorama is the pietà, that is the Holy Virgin Maria holding her deceased son in her lap. It’s one of the great classic themes of Western art history, and as such often parodied in contemporary art.

And even though as a 21st century person I cannot avoid being a contemporary artist, parody could not be further from my artistic goals. To be honest I find it hard to understand how one can be so cynical as to make fun of a scene in which a mother mourns her murdered child, not to mention the divine nature of this child.

I was inspired by our own piece Cricoterie in which you move life-size ball-jointed mannequins around on a theater stage. Playing Cricoterie, I started to imagine what it would be like to hold a body that represents the dead Christ in Virtual Reality. I imagined it could be a very powerful experience. And I adore the idea of working with traditional artistic and mystical themes in computer technology. In this technology I find encouragement to return to the sincerity and the beauty of the art from before the modern era.

Since Virtual Reality hardware and the fast computers it requires are not widespread commodities, from the start I thought of Compassie as an installation. I started prototyping by sketching the setup in 3D.

The player would sit on a large throne-like structure while wearing the VR headset and holding the two controllers. In the real world this structure would look very bare bones. But in VR very detailed and ornate. This throne in fact references many depictions of the parallel traditional scene of the holy mother with her infant son on her lap.

When experiencing this scene in VR I was immediately confronted with an unwelcome problem: it’s very difficult to manipulate bodies in a physics simulation in VR without things getting out of hand. In this case quite literally: it was very easy to have Jesus slip from your lap and fall on the floor in a must undignified manner. This is where the static arts of painting and sculpture have an advantage.

There is a traditional scene in Western art that is very closely related to the pietà: the deposition, or the scene in which Jesus’ corpse is taken off the cross before it is given to Mary.

A form of deposition had always been how I imagined the start of the VR experience: a host puts the body into the hands of the player.

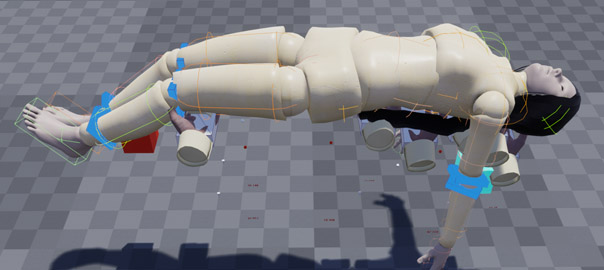

One thing that fascinates about many depictions of the Deposition of Christ is the number of hands that support the body of Christ. It’s always a group activity that involves several people. This allows for the maneuvering of the body to happen in a serene, dignified fashion. This got me thinking: what if the player in VR has more than two hands? What if there’s a hand for each limb of the body but they are all controlled by the two real hands simultaneously. And what if a few of these hands are cherubs?

I did some research into such controls and was relatively pleased with the result. But even though a severely limited the freedom of movement, it was still far too easy to put the body in awkward positions.

I radically simplified the controls by turning the players hands into large cylinders that could not rotate.

I liked this restriction, it felt good in VR, even if the real hands and virtual hands did not correspond completely, since rotation of the hands was ignored. But it suddenly struck me that this dead body feels very light in VR. To solve both problems I imagine I could mount each controller in a relatively heavy sphere that the player needs to balance on the palm of each hand. Such “input devices” would allow the player to feel the weight of the body, ensure a certain slowness and dignity in motion (lest they drop the spheres in reality) while creating better correspondence between real and VR motion.

The simplicity of this prototype also confronted me with a problem that affects many interactive art pieces. When an art work allows you to impact it by doing something, people definitely will do that thing, all the time. Even when the work is more beautiful when you don’t touch it or only once in a while or only in a certain way. No, people will jump up and down, dance like clowns, wave their hands, and so on, in order to see the reaction of the machine. So much so that they forget to even contemplate the art, they’re just playing, moving their body. Not exactly the goal I have in mind.

The original concept included a sort of reward system: if you hold the body gently and still, beautiful things would start happening. Lately I have been a bit annoyed by these types of structures of cause and effect, so I neglected this idea. But now it seemed like such a mechanic could prevention the problem with interactivity described above: Jesus would only appear when you hold your hands still in the right position.

Initial experiments with fading the body in and out were disappointing. It made Jesus seem like a ghost and the mechanic of hold-still-for-display felt a bit too prescriptive, too simple.

Instead of making the body appear from thin air, I want to compose it from elements that are already floating around in the environment. Most of these elements would be undefined fragments but some could be cherubs, or flowers, or ornaments with certain animations. This idea matches up with my original vision of a garden that surrounds the player and starts blooming when they are properly contemplating.

So that’s where I am at now. The first experiements have been a bit disappointing in terms of performance. A few thousand individual pieces with their own behavior still bring a very powerful workstation to its knees. Story of my life: in the twenty years that I have been using computers for creating art, they have never been fast enough to run my imaginations.

But luckily for my mood I have developed this theory that art happens where artists fail to achieve what they really wanted. When they need artifice to compensate for shortcomings in technology or technique, magic appears. So I hope I find some tricks to replace the original idea that ultimately make the piece better. Wish me luck.