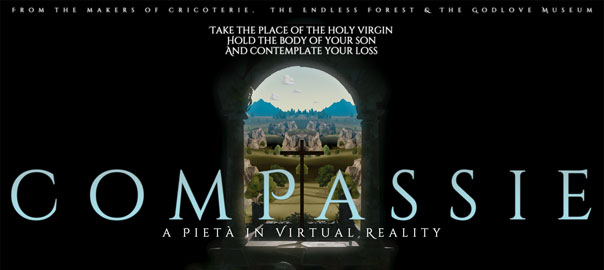

Compassie is the work that I wanted to create. I made it so it would exist. Even if just for a brief moment in time. A whisper in the wind. I knew that from the start. I made it with that intention.

But that doesn’t stop the doubts from pouring in. What am I doing working in a medium that has no future? Why do I choose the most unpopular of themes? Is distributing Compassie for free the wisest decision? Who am I to imagine walking in the footsteps of the old masters? Why don’t I just make my life easy and create contemporary art like everybody else? Or videogames for that matter?

The death wish of technology

When is the last time I have been enthusiastic about a computers? As technology production stagnates around a very small number of monopolies, invention is reduced to the absolute minimum required to ensure survival. And every invention stands or falls by that tiny thread. Virtual Reality is no exception.

Virtual Reality is amazing and I’m happy to have been able to discover it as a creator thanks to a revival of the idea in our times. But since this technology is controlled by large corporations, it does not have a future. These corporations have no real interest in VR, let alone in its artistic potential. They have no vision either because in the current stage of capitalism, vision is a liability. The question is not whether VR has a future but when it will die.

It seems fitting therefore to create a pietà in a moribund medium. It adds to the sadness and the feeling of loss to know that this miraculous technology that allows us to experience fictional worlds in such a wondrous way is destined to die. When you experience Compassie you don’t even know if you will be able to experience it again. Tomorrow, yes, probably. But next year? Maybe. Five years form now? Probably not.

There’s a romantically heroic aspect to this suicidal form of artistic creation. And it pleases like a form of revenge to embrace this medium against all reason and pour an enormous amount of effort into the creation of a wonder that will be blown away by a breeze tomorrow. Like setting yourself on fire in protest. But without anybody paying attention.

The temptation of the present

The logical essence of creativity is doing something that is uncommon, something that others are not doing. Creativity implies originality. Making something that already exists is not creative. I consider art to be a creative act. So art creation implies taking risks, requires doing things that are uncommon, at least in one’s context.

So I decided to be serious. To make a work of art that is sincere and modest. To resist the temptation of the modern age to make light of everything or to overwhelm with spectacle. But I had underestimated how difficult it would be to not make contemporary art.

It would have been easy to add a flashy sci-fi element to my pietà scene, or to contrast the traditional inspiration with hard contemporary irony. And while from the very beginning I knew I didn’t want to do that, the temptation remained great throughout the process. Certainly because to appear edgy or cool would reap more likes on social media 1. But also because I know how to do that. It comes natural to any 21st century Westerner. We love having fun. We loving making fun. For Compassie I had to go against not only the spirit of the time but also against my own nature.

A pietà offers us introspection into sadness. We rarely get the opportunity to be sad, even if we all seem to be depressed all the time. I could offer something here. In Virtual Reality I could create a private space where the user could indulge in their desire to abandon themselves to the sadness to is a constantly looming presence in our lives. A valuable gift for those who take the time, the few minutes required to allow the endless blackness of virtual space to wash over them.

After a long period of prototyping and experimenting with many failing ideas, Compassie ended up being a very easy piece. All it takes is a bit of sensitivity, a bit of stillness. I’m simply asking you to not blow your nose during a theater performance, to not shout in a museum, to not jump around in a church. To give yourself this moment. Two minutes of your life. Give yourself these two minutes.

Two minutes with the dead body of God. Or in fact only one minute because it disappears simply to make its absence more tangible. To turn the knife around in the wound. Because there is pleasure in finally feeling the pain that you knew had been there all the time. Finally realizing that something is missing. The body of Jesus is extremely important. It’s crucial because it demonstrates that God was manifested on Earth in corporeal form. Alive or dead is a detail in this respect.

The beauty of the past

There’s a certain quality of beauty in Renaissance paintings that inspires me greatly. It’s not just the charm of their narratives. There’s also an incredible balance of shapes and colors. A certain fullness, maybe abundance that keeps the eye fluttering about without ever tiring. An abundance that is never exhausted and to which one can only respond with a sort of resignation: alright, I’m here, I’ll stop thinking, immerse me. And one allows the wave of pleasure to happen. I think this effect is achieved by the weight of meaning imbued in the elements in the scene. This tickles the brain into a rational activity that contrasts with the desire to simply enjoy while simultaneously pleasing us that we’re not just enjoying, that we’re involved in something greater, spiritual. We let go, yes, but in a warm and secure embrace.

When I compare those paintings to what I did in Compassie, it’s safe to say that I have failed 2. But that doesn’t embarrass me. It’s like starting to study music when already middle aged: there is no hope that one will ever reach the level of conservatory students. If I’m honest I don’t see any value in my creating art. There is already so much beautiful art in the world. We can just go and look at it and be perfectly satisfied. I know I am.

But I am stimulated by the existence of new technologies that have not been used for the kind of artistic experience that I enjoy. So my work is one of research: can I create a computer program that offers its user an experience that is similar to that offered to me by an old master painting? And I tell myself that perhaps the use of this technology will help my contemporaries to reach this pleasure. And when I’m feeling vain, I imagine that this technology may even be more suitable for it than pigments smeared on wooden panels.

But overall I want to affirm this link of familiarity that I feel with old art. The modern age feels alien to me. I do not understand Picasso, Pollock or Hirst. But Cranach, Van der Weyden and Perugino I get. I know what those guys are talking about. I feel it too. As an art lover, but also as a creator. There’s a direct connection between older art practices and the digital that skips over photography and most modern concepts that erupted in its wake. Because just as the old masters we create realities, and not pictures of realities. We create spaces and characters that live in our world, not pictures of things that happened elsewhere a long time ago. We celebrate existence, we wonder at its miracle, we enjoy its mystery.

The presence of interactivity

In the end Compassie was a simple piece to create. It just took a lot of experimentation and prototyping to discover this simplicity 3. But I think I have learned something now. My plans for the next diorama are very straightforward.

The prototyping phase of Compassie has been a deep experiment with interactivity: a long path to arrive at almost nothing. Motivated by the delicacy with which I felt a dead body should be handled. But with results that are applicable beyond that. In the first prototypes, attention was focused on the body of Christ. Inspired by the handling the ambiguous bodies in Cricoterie, I wanted to make a simulation of holding a body that was explicitly dead, in a context that demands respect and reverence. I assumed that the awkwardness of interacting with objects in VR would have an interesting emotional effect. But it didn’t. So I spend a lot of time figuring out how to remove or hide all the ways in which such interaction could go wrong. A second phase was started with the realization that when the user plays the role of the principal character, the attention must go to the environment, since we do not see ourselves. So I invented an elaborate landscape machine that would change in response to how you treated the body: the landscape would shift through thousands of years of human history when you lift the head of the Son of Man. After a few months, however, it suddenly disappointed me that all the attention went to something not directly related to the theme. In the end, after the body and the environment, I decided to focus on nothing (which I think turns the user’s gaze inwards).

The best answer to many design questions is often “nothing”.

During the experimentation with the cause and effect structures that interactivity implies, I was troubled by how interactivity often feels didactic 4. Rewarding certain actions, even by as little as responding visually to input, stimulates a certain behavior. I don’t want to tell people how to behave or how to feel. Not so much for moral reasons but for aesthetic ones: the pleasure will be greater when the user arrives at it through their own choices and actions. I did cower away a little from this idea. In principle I want to leave it up to the user to play whatever song they want on the instrument that I am offering: it is their own responsibility to extract pleasure from the activity. But I couldn’t bear the idea of Jesus’ dead body being mistreated. So I did my best to limit the possibilities to do so. If safe, I’m not sure if it was the right choice. There’s a problem with freedom in interactive art: there are no customs and there’s no social context. When we know we should not spit at a painting or shout at an actor, we have not really established how digital objects should be treated.

A big part of interactivity in VR is simply presence. What is interesting from an artistic and emotional point of view is not so much what you do with your hands, but how you behave in the virtual space. In Compassie, for example, the direction in which you look is important. It may not be not much in terms of mechanical interactivity, but it can make for an enormous impact. And that’s what matters: the effect on the user.

Technically, my approach to interactivity may have become extremely modest, perhaps reductionist in terms of design. But conceptually it’s not modest at all: it moves much of the responsibility to the user. They have to make it work, they are responsible for their own experience. In this sense my work requires a much greater activity than blindly following instructions. After all, art always happens between the spectator and the work and does not simply reside within the work.

The trouble with music

Music has been a difficult issue. First in terms of decision and later in terms of production. I generally like working with a composer to compose new music for a piece. And I enjoy adapting the atmosphere of my work to what the music evokes. But I couldn’t think of any living composer for Compassie. The music that seemed right to me was music from the baroque era. I did look into contemporary composers who attempt to work in this style but while I found some interesting experiments, nothing seemed suitable. It also feels a bit disingenuous to compose baroque music now. It’s always going to be fake, right?

I have also developed a problem with enjoying recorded music, which has only become more acute due to the lack of concerts during the Coronavirus pandemic. I’m an amateur musician myself. I play the classical guitar and the viola da gamba. And even though I am not very good at it, I enjoy the feeling in my body of sound produced by an acoustic instrument in a physical space. Likewise I enjoy attending concerts, preferably on the first row, almost surrounded by the orchestra. To be present in that universe of sound is so much more than just listening to music.

But in my medium, the computer, I am forced to used recorded or generated sounds that will be reproduced through speakers. It hurts me to have to do this to music, to sound. Especially, I think, because of the contrast with how I feel about the experience of my art: the diorama is a living environment, and experiencing it is a sort of performance, a unique event.

When developing the original ideas for Compassie, presenting the work as a physical installation was an important part of the concept. And in such situations, I would have the experience of the user be accompanied by live music on the viola da gamba (the resonant and mournful sound of which fits a pietà splendidly). But the Coronavirus pandemic ruined that idea. Even when we will all have been vaccinated and live events become normal again, I don’t know how we will feel about sharing VR goggles in public places.

Around that time, I was studying the intro of Stabat Mater by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi on viola da gamba. A piece, by the way, that I discovered when looking for music for the very first Tale of Tales game that was never released. It has a very compelling bass line for cello that was easy enough to play on the viol. I especially enjoyed playing it an octave lower on my 7-string instrument. So I started experimenting with that little piece of music in the Compassie prototypes, initially only using samples of bell sounds, because I fondly remember the intricate effect of them in the first prototype of Cathedral-in-the-Clouds. Since I couldn’t have a musician be present, I chose the next best thing: I created a software musician.

When I experimented with a fixed soundtrack it felt too flat, compared to the giant space the event took place in. So I developed a system that would play each note at a random location in space, different every time. Basically a little sequencer programmed to play one beat of the music every x seconds.

Later I took advantage of the silence of the Coronavirus lockdown to record all the notes for the bass line on viola da gamba. But I kept the bells for the high voices. They sound strangely disconnected without the bass line, almost random, and that fit perfectly with the feeling of staring into the void.

The choice for obscurity

I stopped making commercial videogames six years ago with the purpose of making things like Compassie. I would never have been able to make Compassie if I had thought about it as a game that would be offered for sale. There’s too many cooks in the kitchen of my head when that is the case. All I wanted for Compassie was to be something that deserved to exist.

A side effect of giving art away for free is that it is ignored. We learned this in the game industry early on. Few people noticed our first release, The Endless Forest in 2005, which is still available for free. So for our second game, The Graveyard, we experimented with commerce for the first time. And suddenly the games press paid attention. The situation in the art world is different but somehow most discussions about contemporary art tend to center around money too, the current wave of non-fungible tokens being no exception whatsoever.

So I knew from the start that creating a piece that was going to be distributed for free meant that it was going to be ignored. But I tried thinking of that as a good thing 5. My desire was to simply create this work. I had no desire whatsoever to promote it. And frankly there would be no point. Things get attention in as far as they are conventional. Maybe after the pandemic when I can present Compassie as an art installation in a museum, somebody will care. But the thing is: Compassie moves me. No other work that I have made has had such an impact on me.

I am reminded of the previous piece that I made just for myself, ten years ago. While creating Bientôt l’été I was torn between the desire to appeal to an audience (of gamers) and the desire to explore the aspects of the medium that fascinated me. That doubt is gone now. If only because I wouldn’t even know who the audience for VR is.

“Working in a popular medium as videogames where serious cultural consideration is rather scarce, I’m always torn between the desire to do the work I know I should be doing and to make things that are easier to enjoy for the existing audience of said medium.”

Michael Samyn, development journal, 2012

After Bientôt l’été, I felt embarrassed. Embarrassed about the self-indulgence. And I decided that I would stop making such selfish things. But a decade later here we are again. I’m not embarrassed this time. But I do wonder if it makes sense to make art that nobody sees. On good days I think of it as a prayer. God sees everything and that should be enough. Even for a non-believer. I think Compassie is beautiful. Can that be enough? Can I simply make things that I find beautiful?

I don’t want to not care about my work. I want to tell the world about it and give everybody the opportunity to experience it. I love hearing the thoughts of people about my work. But I don’t want any feedback in terms of numbers. Knowing how many, or rather always how few because no number is ever high enough, is detrimental to my spirit and my motivation. For me Compassie is already a success: I finished it, it’s beautiful and it makes me feel things. That is my only goal. I get frustrated when people tell me that my work should be more well known. I agree. But should that be my responsibility when activity towards that has such a negative impact on my creative ability?

Compassion for the sad

Compassie is the first piece I made on my own in a very long time. I mean without Auriea Harvey with whom I have collaborated for almost two decades. I’m happy to have found three wonderful artists to collaborate with on Compassie (Jessica Palmer, Moné Sisoukraj and Zoe McCarthy). I like collaborating. I don’t like being the only author of a piece. I’m not an individualist. I’m a product of space and time. And for a while I was able to dissolve in a union with a partner. But Tale of Tales is dead. Song of Songs is a fitting new name: a poem about separation and longing. In part, the sadness that Compassie indulges in, is sadness for this loss. The god that we once were is dead. Though I doubt that this sacrifice will save humanity.

But Compassie is much more than that. It’s not really about sadness, it doesn’t generate sadness. It’s a place where you can bring the sadness that’s already inside of you, any sadness. Maybe in the end the beauty of Compassie is that it gives compassion to you, the user. More so perhaps than demanding it from you for its subject, as the traditional pietà might. By allowing you to indulge in your sadness, it expresses compassion. It’s alright to be sad here. You have plenty to be sad about. There is no shame here, no guilt. You are sad. Come here, and be sad. Just, be sad.

—Michael Samyn.

(1) We live in a time of numbers. And the numbers make us feel like failures. Because there’s always something that gets higher numbers. And it is invariably something that doesn’t seem as interesting as your own. To the point where we almost have to consider quantity to be diametrically opposed to quality: the more popular, the worse the art. If this is childish then it fits perfectly with the spirit of social media which turn us all into envious teenagers trying hard to seem cool.

(2) In my stubborn devotion to sincerity I may have fallen into the trap of austerity. I may have fallen in love with the void too much and forgotten about the sensations of sensuality that pervade even the most terrifying works of the old masters. I may have made it too easy for the user to be satisfied, to be fulfilled. There’s not enough unanswered questions. Literally: not enough. In my next piece I will pay attention to quantity. It’s more important than I thought.

(3) It seems normal that a new creative technology would invite a lot of artistic research. But in the current social economic climate this is just not the case. We have seen this in web design, in videogames and now it’s happening in virtual reality. Or rather not happening. Most of what we use new technology for is trying to do the same thing we did with slightly older technology. So we make books in websites, board games in videogames, and videogames in VR. To the point where it seems like every time we may be discovering something interesting in a some technology they make it obsolete by inventing something that allows us to start back from zero, where we feel more comfortable.

(4) I consider art with a message to be propaganda. And I do not have a high esteem for propaganda. I consider more valuable an art that allows me to explore myself and the world, and the ideas that connect the two. For that reason the artist needs to refrain from communicating too much.

(5) Sometimes I wonder if there’s something wrong with me, psychologically, for not wanting to be successful. Is this fear? Am I a coward, afraid of failure? But my real problem is that I actually do have a desire to please people but that I’m simply not very good at it. And what makes matters worse, and unacceptable, is that my art suffers under my attempts to please. I can only make things like Compassie when I devote myself to the work. When my only goal is beauty. This is my sacrifice. I nail my vanity to the cross. And I weep. And I pray.