We have always felt a kinship with the Old Masters. Since we use computer technology in the modern age, our interest in such analog art forms, figurative presentation and often religious subject matter may strike as odd. But next to the practical similarity – we use the high technology of our time, just like the early oil painters did – we also share an interest in what I like to call the synthetic image.

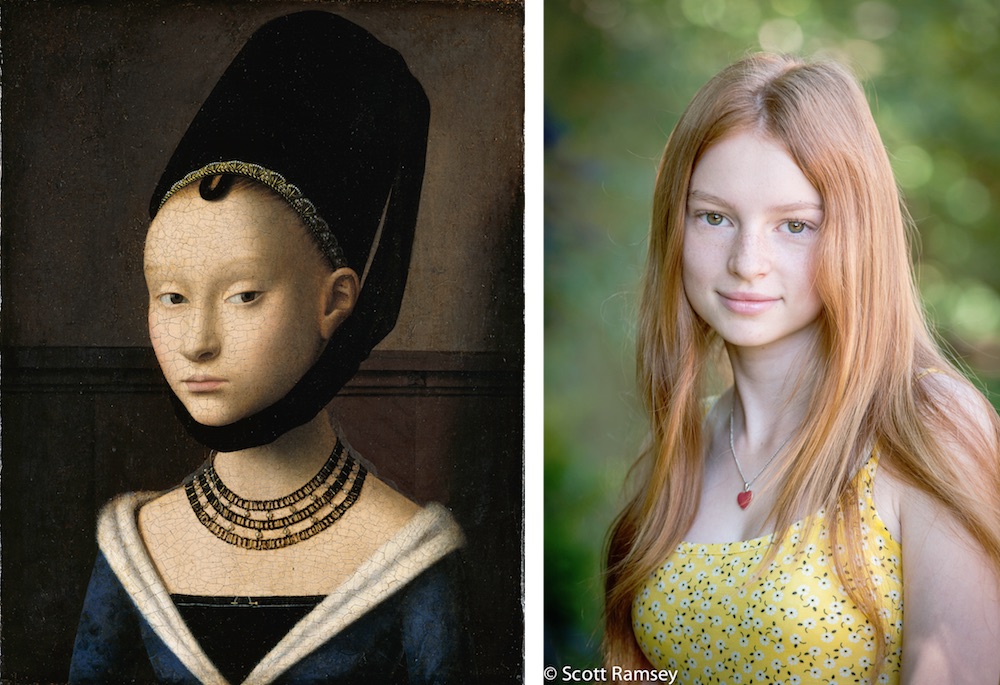

The synthetic image is created by a human. It can be, and often is, modeled after life but the shape and color and texture are entirely man-made. Somehow such images can possess a power that goes beyond any image that is created mechanically, either directly through photography or with significant aid of optical instruments.

This is not a theoretical principle for me. I have learned through experience that synthetic images tend to affect me more. I don’t know if this is true for other people as well.

Maybe a synthetic image can be so powerful because it is a subjective creation that appeals to the subjective perception by a spectator. A mechanical image, created through photography for instance, on the other hand, is never entirely subjective. There’s always an inhuman aspect to it. Maybe that creates a distance that reduces the power of the work.

The curse of photography

Long before photography, painters developed the realism of their work. And while paintings from the baroque, rococo and salon periods certainly have their charm, they never move me quite as much as early paintings do, with their wonky perspective and skewed proportions.

When photography grew out of the desire for realistic depiction, it more or less ruined figurative painting. In a very direct way it coincided with the birth of abstraction in art. One can imagine many painters wondering about the point of painting figures or landscapes when there was a mechanical device that could reproduce reality in a fraction of the time and with a fraction of the effort. And maybe it is only now that photography has become intensely ubiquitous that we can start to understand the great value of non-photographic, synthetic images.

Photography is a wonderful tool. And out of photography some great new art forms were born. But it has ruined the more traditional forms of depiction. Even when artists today draw and paint figuratively without referring to any photographic images, their work never affects me as much as the old art does. Because something about it still reminds of photography, which hollows out the experience. Photography has changed the way we look at reality. So much so that it has become difficult for us to create a representational image that is not infected by the photographic eye.

A painting that looks like a photograph is always disappointing to me. Instead of experiencing a transcending, universal, symbolic image, we see a picture of some guy or some woman. Flat, meaningless, empty. And no matter how hard we try, we can’t escape the impact of photography on our eyes.

The power of creation, and the opportunities offered by realtime 3D

I think the computer offers a way to escape the stranglehold of photography: through realtime 3D. Just like the pre-photographic painters, computer artists create images out of nothing. We place vertices in virtual space, connect them with lines and fill up the triangles between them. We can’t really use photographic references because we are working in three dimensions and because the computer demands specific construction methods to allow for processing.

When I study early renaissance painting, especially the Flemish Primitives, I sense that they too were thinking of their practice more as modeling virtual worlds than creating pictures of reality. The religious subject matter helped the desire to transcend the mundane. And the newness of the technology stimulated invention. Those early paintings are as much about evoking physical sensations of material and space as they are about creating shapes. All of this is familiar terrain to the realtime 3D artist.

Realtime 3D offers us once again a way of creating synthetic images, potentially with the same power of early painting. This does require a conscious effort of the artist to move away from the photographic image and towards a more symbolic one. We need to resist the temptation to imitate reality offered by a technology built by engineers with no pictorial imagination. Because then all we have is that reality. And not something that transcends it.

The computer screen, with its two dimensions, is not our canvas or panel. We are creating realities in virtual spaces. Virtual spaces that are alive through the processing power of the computer. We are not creating images but objects (much like sculptures, but even paintings are objects! –unlike photos which are prints on paper or light on screens). Even if there is no visible difference (when displaying our work on a screen), our objects continue to really exist in the virtual (unlike photos or films that are only pictures of a reality that does not exist anymore).

The experience of art, or being in the presence of the work

I have never had a deep aesthetic experience with a reproduction of a painting. The magic only happens in the presence of the actual object. It doesn’t even need to be the original work – this is not fetishism – but it needs to be a real painting or sculpture. Photographic reproductions don’t work for me.

Even though realtime 3D does not possess the physical properties of painting or sculpture, a similar effect can be observed. Realtime 3D exists in another type of reality: it is running – right now – on a computer.

One needs to be in the presence of the real work of art to have a deep aesthetic experience. Digital art is real when it’s running on the computer’s processors. Rendering kills the art. Screenshots don’t work, even videos don’t have the same effect (linearity kills realtime). We have to be in the presence of a software application that is running now, in the same time as the one we inhabit, for the art to affect us deeply.

And we need to embrace the synthetic nature of these artworks. By constructing realities out of nothing with means that circumvent the photographic way of seeing, we can, once again, approach a power and mystery of art.

—Michaël Samyn.