I started this second phase of work on a Virtual Reality pietà scene with the following concerns.

I’m trying to avoid the undignified effect of errors in both human use as machine function. But errors and clumsiness were in part what attracted me to this theme. Holding a dead body is awkward. It is difficult physically. Especially for a (older) woman to hold the body of a grown man. And it is odd mentally, because we feel we owe this corpse an enormous amount of respect while it cannot respond and we are in control of its motions.

But while I am quite sure anybody would handle this situation gloriously in real life holding a real dead body, the same is not true in VR. In a simulation we know things are fake. We’re in a magic circle where we can experiment with irreverence. The opportunity to interact with a human body beyond the repercussions of every day society is alluring. Moreover we love interaction as such, we are fascinated by machines responding to what we do. We want to see what happens when we do something or other.

There is no way that a work of art can demand the same reverence as a dead body. Art is play. Even when it deals with serious themes. Art functions only when we play. We enter the art through play. We have to participate.

While sculptures, paintings, films and poems completely ignore whether or not you’re playing them right, an interactive work of art can actually know if you are. And we can make it respond to this data. So there is a temptation to attempt to force a proper experience. But is that wise? Other art forms leave it up to the player. And the only judging that happens is social. If you burst out laughing in front of a crucifix, a Rothko or and photograph of a starving child, you can expect a reaction from people around you. But the work of art does not change.

In a simulation, however, the art can be changed. The player’s interaction could create a grotesque situation in the virtual space, one that may in fact be humorous. Ideally, in my general philosophy, this should be accepted. Real-time art is for exploration and the creator should not prescribe too much or expect anything specific. If the player decides to fool around, it’s their loss. The problem is that this seems to apply to most players. Maybe interactive art is really only suitable for lighthearted entertainment.

And even if the player would devote themselves earnestly to the exploration, there still remains the computer that makes mistakes all the time. Accidents happen. The simulation starts freaking out, often causing a horrific effect that we can only protect ourselves against through laughter.

I decided to abandon my initial inspiration of clumsiness. I figured I should remain flexible and respond to what happens during creation. After all, this is still a very new art form, and definitely very new to me. Just because a simulation can be interactive doesn’t mean it needs to be. There’s a lot of unique value to realtime art outside of interactivity. The only thing that matters is giving the player an experience of beauty. There is nothing to prove. No statement to make. No debt owed to technology. No pride or arrogance or purity.

The player plays the role of Virgin Mary. The corpse of her adult son Jesus is on her lap. She can move her arms to lift up the body by the shoulders with the right hand and by the knees with the left. When I simplified the interaction radically to lifting the right arm very slowly up and down over a distance of about 40 centimeters I felt exhilarated. It feels pleasantly naughty to design such minimal interaction in a medium of which interactivity is often considered its pivotal component. But the thing that made it really work for me was slowing down the response. The body is not lifted up with your moving hand, instead it follows the hand very slowly. This encourages one to slow down one’s own movement. And this slowness of motion gives a feeling of weight, solving that other problem. I’m calling this ambient controls.

Part of the initial design of this project is that the environment changes along with your behavior. So the world would become bright when you lift up the head towards your own and dark when you allow the body to fall back into your lap passively.

But with the radically simple interaction came an in hindsight obvious realization. When you cast the viewer in the role of the subject of a scene, the environment around them becomes more important than the main character. The latter in fact becomes as invisible as the viewer’s own body is to themselves. Suddenly my attention shifted to the environment that surrounds this scene.

Now I want this simple gesture of moving your arms 40 centimeters up or down to take you through the 12000 years of human civilization. From the electric darkness of the Anthropocene to the sunlit harmony of the Garden of Eden. I was inspired by how Timothy Morton in Dark Ecology points out that Genesis can be read as a justification for (or lamentation of) agricultural civilization. And the side effects of the Corona virus crisis gave us all a glimpse of what the planet could be like without the impact of industry. It was like traveling through centuries in just a few weeks.

As I was dealing with such dramatic content, I felt drawn once again towards the Flemish Primitives, the artists whose works initially inspired the Cathedral-in-the-Clouds project. Especially Hieronymus Bosch’s depictions of the whole of human history from creation to apocalypse. So I made this desktop wallpaper based on the top of the left panel of the Garden of Earthly Delights, which represents the Garden of Eden. Since the panel is vertical and my monitor horizontal I decided to mirror the tiles to make a continuous picture.

Two things came out of this.

First I noticed Bosch’s use of perspective. As in many Northern Renaissance paintings, the landscape seems to be depicted from above while the objects and characters are seen from the side or the front. It only feels weird when you start noticing it. The picture still immerses despite of this lack of realism.

right: Hieronymus Bosch, Garden of Earthly Delights (circa 1500)

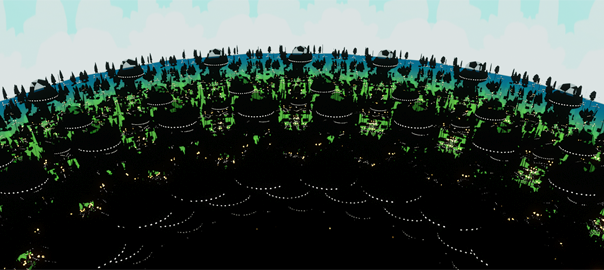

I had been bothered a bit by how the naturalism of a horizon on eye height in VR caused half of the scene to consist of sky. And there’s nothing happening in the sky. Everything happens on the ground. Bosch’s solution is genius: put the horizon at the top of the image so you can show all the things happening on the land. I can achieve a similar effect if my ground in VR is in fact a hollow hemisphere in which the viewer is positioned quite low. In combination with some scaling of the elements drawn on this hollow ground a rather pleasant fake sort of perspective appears.

I never thought of the environment in this piece as being a naturalistic. Instead I wanted something ornamental, as one can often see in early paintings and tapestries.

My desktop wallpaper suggested a method of creating decorative patterns out of figurative elements: through repeating and mirroring. As a bonus I would only need to produce one segment of a world and then simply repeat it.

Of course, in the sphere of computer creation there is no such thing as simple. All this technology barely works if you try to do anything other than what its unimaginative creators want you to make. Which in this case would be static environments. But my world needed to be highly dynamic: I want to browse through 12000 years in the lift of an arm. From my previous experiments with dynamic objects I had learned that in 2020 computers still can’t handle a few thousand of them simultaneously on screen. Except, I realized, for particle systems! Originally presumably invented for simulating explosions, smoke and fire, particle systems could do all sorts of things these days.

As it turned out a new particle system technology, called Niagara, was being added to Unreal Engine. Since I did not want my work to disappear when they phase out the current technology, I started learning how to use it. It’s quite a powerful system with a reasonably adequate interface. But I did run into some problems, even a bug, that hopefully will be resolved soon.

To aid in my experiments I needed some assets. I figured cubes and spheres would not help me make aesthetic decisions. So I imported some of the models and textures created by Mary Lazar based on concept drawings by Vicki Wong for our sadly cancelled project An Empty World. An Empty World is also structured along a transition from natural to cultural and industrial landscapes.

To end this little report, please enjoy some screenshots of the current state of the project taken in the Unreal editor, because the aforementioned bug causes none of this to show up in an executable build.

Providing the technical issues are resolved, I consider the design of Compassie done. Can’t wait to start production and bring it all together!

Thank your interest in my process.

—Michael Samyn.