Only the devil can make anyone believe that Christianity is false.

All posts by Michaël Samyn

Confessing that we are sinners is nothing more than admitting that we are imperfect. And naming our sins is simply figuring out the areas where we could improve. In the sacrament of reconciliation we receive the strength to grow closer to perfection, to holiness, a state we can only fully achieve after death.

Without Christ we’re basically just managing emotions. We try to avoid feeling bad. And when we do feel bad we try to get rid of the feeling through breathing exercises or relaxation, maybe meditation or even vacation, or simply distraction or sleep. Until we feel good enough again to go on living. There’s no reason why we want to prevent or remove the anger or the jealousy or the sorrow other than that it doesn’t feel nice. We’re afraid of bad feelings so we avoid situations that could provoke them. This is how we live without Christ. On a desperate rollercoaster beyond our control.

Conversation with a modern atheist:

“If you were very rich, would you pay for a therapy that would make you live forever?”

“Absolutely!”

“What if it were free?”

“No, then I’d rather die.”

The question is not if you want to go to heaven after you die. The question is if you want to go now.

Even if Jesus only imagined that He was saving you when allowing Himself to be tortured and executed, He deserves your respect. You could call Him a fool for thinking that His suffering would unlock your happiness. But doing so He loved you more than anyone ever has or ever will.

The Endless Forest II beta 5

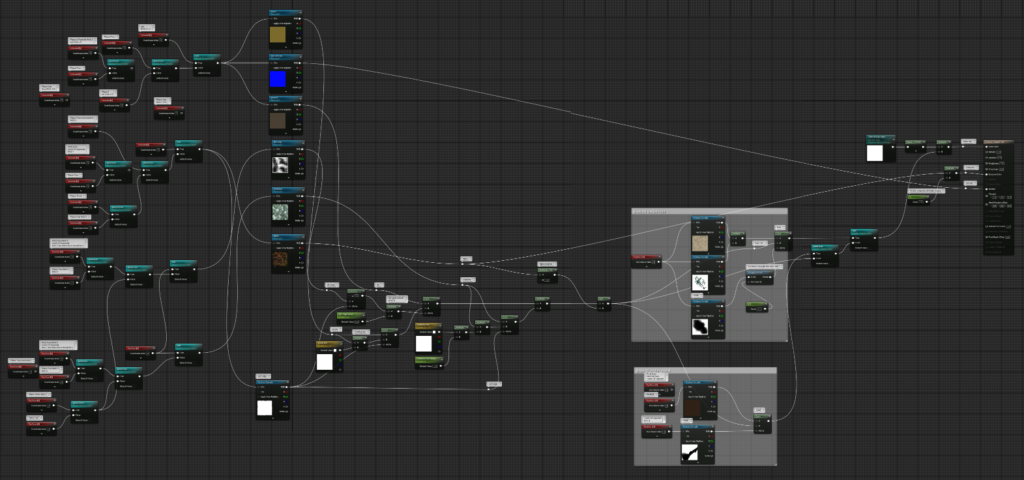

The process of building and packaging a multiplayer game in Unreal Engine is a complicated affair that involves hundreds of thousands of files stored on many gigabytes worth of hard disk space. Creating a single build can take hours. So errors are expensive. And with every new version of the engine new errors occur. So one can only half rely on past experience. It’s a huge challenge every time.

This time an additional problem occurred when the processor of our good old server machine turned out to be incompatible with the new game. So I decided to try a new server host for sharing this release.

Nevertheless I was very eager to share the work done in step 26. So, after fixing some remaining bugs and perfecting the Halloween features, I started the process that ultimately lead to beta 5 being available for your evaluation.

Download links have been emailed to supporters of the remake. I you would not have received yours, please contact us.

The Unreal Forest: step 26

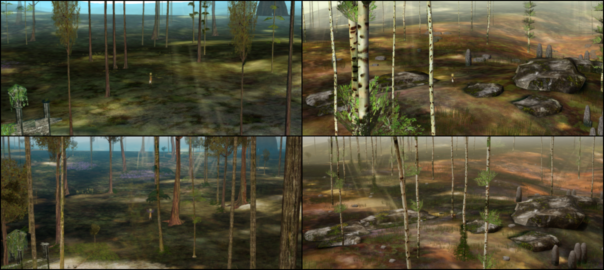

Motivated by bug reports and criticism of players following the release of beta 4, I started to tweak the remake of The Endless Forest so it would resemble the original game more. The two areas I focused on were controls and aesthetics. I’m happy with the changes I made to the controls but ran into a lot of trouble trying to make the game look in Unreal Engine the way it does in Quest3D. Part of the reason for this is that we painstakingly adapted the look of the game to the rather primitive rendering capacities of that old engine. In my frustration I decided to just make the game look good in Unreal and not worry about whether it resembled the original or not.

I started with the material used on the floor. Since the view of the game is top down most of the time, the floor has a great impact on the overall look of the game. I reused the textures from the original game but increased their resolution through an AI-driven process in an application called Topaz Gigapixel AI. I was quite impressed by the new detail in the high resolution textures. There’s textures for dirt, grass, light and shadows that were blended in a very specific way in Quest3D, unavailable in Unreal Engine. Instead of attempting to mimic that system, as I had before, I started over from scratch, with the same textures, but using blending methods specific to the new engine. I also added some relief and detail through normal maps generated by NormalMap Online based on the original textures.

It took several days and several start-overs to get a result that I liked only to realize that now seams were visible between the tiles that make up the floor. I discovered these were not only caused by the uprezzing of the textures, but the new shader also made visible UV mapping errors that had not been visible before. So I corrected these in Blender.

In beta 4 the shadows were colored by three extra lights shining in the opposite direction of the sun light, imitating the natural effect of bouncing light. I replaced this by a Skylight element.

None of Unreal’s built-in methods for simulating fog was capable of hiding objects in the distance. As a result, geometry popped in abruptly when crossing forest borders. This was fixed by replacing the fog by a shader on a plane in front of the camera that colored objects based on distance. Sometimes primitive methods work better that attempts to simulate physical reality.

To complement the increased resolution of the floor textures, I also uprezzed the textures of the ruin, the playground, the watering hole and the trees and added generated normal maps.

The camera angle was also tweaked slightly to resemble the original game more. And the controls for walking, jumping and interacting with obstacles were also fine-tuned for smoothness.

The strange error of the swimming frog floating in the pond was also corrected.

I tweaked the shader of the tree foliage to become transparent when it is in front of the camera in order to have a better view on the deer.

At the end of this process the overall look of the game was actually similar to the original when I reduced the contrast in post processing. So I added a slider in the game’s options to change the contrast. Personally I think the goal of making The Endless Forest look better than the original has been achieved. But I will let you be the judge of that.

Note that trees and plants are placed in a very different way in the remake. Instead of the wonderful system available in Quest3D that allowed us to manually place threes and decor, I created a system in Unreal that places trees randomly within certain parameters. This is why they don’t appear in the same locations. The advantage of the new method, while we lose some of the deliberateness of the original, is that the forest can change in the future and that the density per area, similar to the original by default, can be increased by the player. The resolution of many textures was increased through AI but the 3D models remain the same as in the original.

I didn’t feel ready to release a new beta version because there’s still a number of bugs and issues I want to address first. And because I’m going on honeymoon.

Let me know what you think!

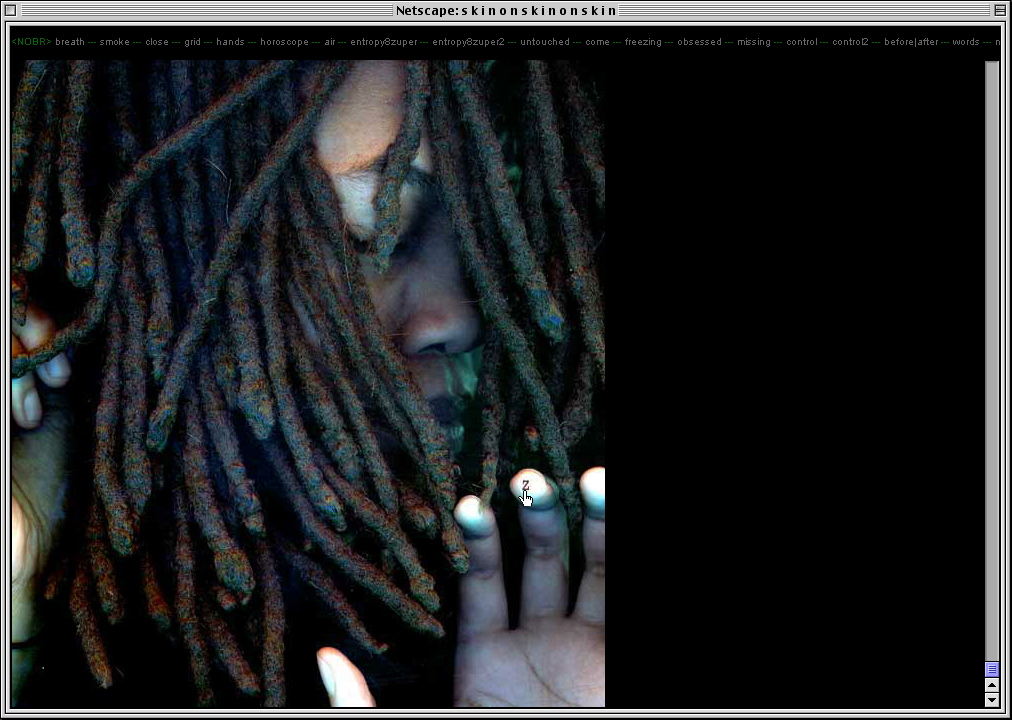

Auriea Harvey: My Veins Are the Wires, My Body Is Your Keyboard

From 2 February to 7 July there will be a giant exhibition about Auriea’s artistic career in the New York Museum of the Moving Image, starting with sketchbooks from the early 1990s all the way to new digital sculptures created for the show. Since during a large chunk of that period (from 1999 to 2019) we were working together, a lot of the pieces in the show are collaborations: web projects by Entropy8Zuper! and videogames by Tale of Tales.

The exhibition will focus on her contributions to our work, which have always involved digital sculpture. While mine (interactivity, atmosphere, soundscapes, etcetera) have become somewhat of a lost art. After the web was ruined by social media we stopped creating art for the web and switched to videogames. And when those were ruined we quit videogames too. Initially in favor of Virtual Reality but that seems to be over now as well.

Auriea was able to make the step towards the world of contemporary fine art and continue her artistic activity in that context. But I have not. Digital art has, from the beginning, been a way for me to stay away from the world of modern art in favor of direct contact with an audience made possible by the internet. I was also seduced by and am still very fond of the unique possibilities of the realtime medium that cannot properly be experienced in the traditional fine art context and for which no other platform was ever developed.

But the most important reason why I stay away from the art world is me. I don’t respond well to the challenges posed by the contemporary art world. I don’t like who I become in confrontation with an environment that I experience as cynical, shallow and driven by money and power and dogmatic politics. But above all, I’m afraid I don’t like most modern and contemporary art. And I don’t enjoy being in an environment where I dislike the work of most of my colleagues. It was fun for a while when I was making games but I guess I feel too old for that kind of easy rebellion now.

For me, Auriea’s exhibition crowns my new faith. Three years ago I converted to Catholicism. Christianity has taught me a way of living and loving that has made me a much happier person. As an atheist I would never have been able to tolerate the injustice of an exhibition of our collaborative work presented as hers alone. I would have been so angry. It would have probably lead to a divorce. But as a Christian I’m happy to disappear. It’s the eagerly desired response to my many Litanies of Humility. And it makes me profoundly happy to find myself capable of enthusiastically supporting my wife. We recently got married in church. And this exhibition, or at least my modest role in it, extends our holy matrimony: she is the Bride, the Holy Jerusalem, adorned and pure. I am her servant. I lay down my life for her. This is all I want. This is who I am. Finally.

Michael.

The Endless Forest II beta 4

I was hoping to release this version to the public at large. It worked well and looked good on my computers. But to be on the safe side, I decided to release it to the community of players of the current game first. Just in case some minor issues needed tweaking before a public release.

Thanks to the diligent research of several Endless Forest players, a flood of bug reports rolled in, making it abundantly clear that this build, even for a beta release, is by no means ready for the public at large.

Many issues, sadly, seem to be related to performance. Apparently the 2005 engine of the old game runs better on many computers than that latest Unreal Engine 5. That’s a disappointment!

I know I’m getting older and might be slightly jaded after half a life time working with computers, but technology seems to evolve in a direction away from what we used to call the “personal computer”. Creative software seems to be geared more and more towards large commercial corporations and big budget projects. I like using Unreal Editor but, especially for an mmo-type game like The Endless Forest, it’s an unwieldy monster. To simply make a build of the game takes a week because of all the steps the process entails, and the massive amount of data generated. Even in the end, the compiled game which is exactly the same as the old one, is a ZIP file of 270 MB and requires a bunch of runtime prerequisites. While the old game is slightly over 50 MB. No need to say that this slows development iteration down. Especially in a one-man operation. I’m sure big companies have all this stuff streamlined and distributed over several departments. But for single creators making anything other than a drawing, a piece of music, a video or a 3D model, has become extremely challenging.

The Endless Forest, however, is beautiful. And I believe it deserves to exist. More and more so, even now. So I’m grateful for the effort that many players have put in. Pray for me that I can figure out how to fix all these issues.